Destiny.

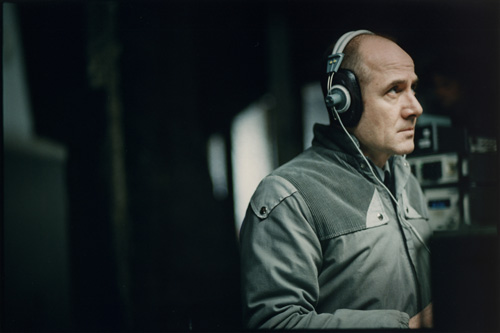

Destiny.With its beautifully multi-layered drama and its great sense of closure, "Three Colors: Red" is quite easily the best film in Krzysztof Kieslowski's "Three Colors" trilogy. It stars the beautiful Irene Jacob as Valentine, an easy-going fashion model, and Jean-Louis Trintignant ("The Conformist") as an enigmatic retired judge who eavesdrops on his neighbors' private lives by way of wire-tapping their telephones and successively playing them in his speakers as if a series of radio shows. Although the relationship between Valentine and the judge is peppered with psychosexual tension, which my more cynical mind, to a certain extent, reminds me a lot of the relationship between Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter, the film, albeit the enveloping intrigue and mystery that surrounds the whole film's premise, is a hopeful exercise in love and human warmth.

Out of the three films, I think that "Three Colors: Red" is the most immediately relatable but at the same time also the most cryptic (the questionable actions of the retired judge). We can relate with the adventurous Valentine because, unconsciously, we are also her because by any chance our car may ran over a dog and find out that the wounded animal has a name tag with an address in it, we will immediately return it to the owner, which in this case is the judge. This is how Valentine and the mysterious judge met, therefore forming a bond forged out of curiosity and developed out of the immediacy of human connection.

For some filmmakers, with this kind of characters, a twenty-something girl and a sixty-something man, it's enough grounds to create a relatively pretentious romance. But Kieslowski, himself about to reach sixty years of existence himself (which he never did when he suddenly died in 1996) by the time this film, his last one, was released, knows better by instead playing this type of character relationship with dramatic assurance, wisdom and lots of heart. Of course, it's not without a hint of tragedy and a sense of isolation, which both "Three Colors: Blue" and "Three Colors: White" has finely established in different perspectives.

But aside from this filmic relationship, Kieslowski also has something much trickier to pull off: how to coherently tie up the three films while also giving his current characters enough breathing space to wrap up their own situation.

On one side, we have the budding emotional involvement between Valentine and the privacy-invading judge. On the other, there's also a young judge named Auguste (Jean-Pierre Lorit), whose life, in many ways, closely mirrors that of the judge's and who's currently involved in a run-of-the-mill romance with a personal weather reporter.

At surface viewing, "Three Colors: Red" may look like your typical film by way of how it tackles love and existence at different viewpoints, sometimes in bliss, sometimes in pain. But Kieslowski has created his characters to fit an urgent inevitability to unconsciously interconnect. In this idea of intertwining of fates, Kieslowski has already gave us a tease by mistakenly letting Julie (from "Three Colors: Blue") enter the courtroom where the divorce trial between Karol and Dominique is taking place in the beginning of "Three Colors: White". There's also the hunched old lady (who appeared in all three films) immersed in a mundane difficulty: The camera and the characters always catch her laboriously trying to put an empty bottle inside a trash bin; a prominent figure in the whole trilogy that has been, in a way, the barometer of the protagonists' characters. (Julie merely looked at her in puzzled sadness while Karol minutely smirked at her predicament. Only Valentine has the basic courtesy to help her put the bottle in the bin).

In this film, it has truly, as they say, come in full circle.

But not in the way how a generic ensemble film may. Sure, the film may have discoursed about the general outlook of love by way of those two (bliss and pain) extremes, but the film is a minuscule observation of love and life at the same time as it is a far-reaching, 'what if' meditation on time. In the end, "Three Colors: Red" relies on the singular choices and plans of its characters instead of giving the responsibility to an invisibly omniscient hand to move the likes of Valentine and the judge as if indifferent chess pieces. And for that, the film was uniquely pragmatic.

After 'liberty' and 'equality' were tackled through individualistic perspectives by way of Julie and Karol in the two previous films, "Three Colors: Red" was able to brilliantly put these stories, stories of people striving through all too human flaws, in a holistic harmony even in the midst of a tragedy. This may very well be the significance of 'fraternity' in the whole film, but "Three Colors: Red" is also quite aware of another infinitely more transcendent thing: destiny. Again, with its fascinating visionary depth and articulate human drama, "Three Colors: Red" is the best film in the trilogy, and is also a fitting swan song for Krzysztof Kieslowski, who sadly passed away far too soon.

Out of the three films, I think that "Three Colors: Red" is the most immediately relatable but at the same time also the most cryptic (the questionable actions of the retired judge). We can relate with the adventurous Valentine because, unconsciously, we are also her because by any chance our car may ran over a dog and find out that the wounded animal has a name tag with an address in it, we will immediately return it to the owner, which in this case is the judge. This is how Valentine and the mysterious judge met, therefore forming a bond forged out of curiosity and developed out of the immediacy of human connection.

For some filmmakers, with this kind of characters, a twenty-something girl and a sixty-something man, it's enough grounds to create a relatively pretentious romance. But Kieslowski, himself about to reach sixty years of existence himself (which he never did when he suddenly died in 1996) by the time this film, his last one, was released, knows better by instead playing this type of character relationship with dramatic assurance, wisdom and lots of heart. Of course, it's not without a hint of tragedy and a sense of isolation, which both "Three Colors: Blue" and "Three Colors: White" has finely established in different perspectives.

But aside from this filmic relationship, Kieslowski also has something much trickier to pull off: how to coherently tie up the three films while also giving his current characters enough breathing space to wrap up their own situation.

On one side, we have the budding emotional involvement between Valentine and the privacy-invading judge. On the other, there's also a young judge named Auguste (Jean-Pierre Lorit), whose life, in many ways, closely mirrors that of the judge's and who's currently involved in a run-of-the-mill romance with a personal weather reporter.

At surface viewing, "Three Colors: Red" may look like your typical film by way of how it tackles love and existence at different viewpoints, sometimes in bliss, sometimes in pain. But Kieslowski has created his characters to fit an urgent inevitability to unconsciously interconnect. In this idea of intertwining of fates, Kieslowski has already gave us a tease by mistakenly letting Julie (from "Three Colors: Blue") enter the courtroom where the divorce trial between Karol and Dominique is taking place in the beginning of "Three Colors: White". There's also the hunched old lady (who appeared in all three films) immersed in a mundane difficulty: The camera and the characters always catch her laboriously trying to put an empty bottle inside a trash bin; a prominent figure in the whole trilogy that has been, in a way, the barometer of the protagonists' characters. (Julie merely looked at her in puzzled sadness while Karol minutely smirked at her predicament. Only Valentine has the basic courtesy to help her put the bottle in the bin).

In this film, it has truly, as they say, come in full circle.

But not in the way how a generic ensemble film may. Sure, the film may have discoursed about the general outlook of love by way of those two (bliss and pain) extremes, but the film is a minuscule observation of love and life at the same time as it is a far-reaching, 'what if' meditation on time. In the end, "Three Colors: Red" relies on the singular choices and plans of its characters instead of giving the responsibility to an invisibly omniscient hand to move the likes of Valentine and the judge as if indifferent chess pieces. And for that, the film was uniquely pragmatic.

After 'liberty' and 'equality' were tackled through individualistic perspectives by way of Julie and Karol in the two previous films, "Three Colors: Red" was able to brilliantly put these stories, stories of people striving through all too human flaws, in a holistic harmony even in the midst of a tragedy. This may very well be the significance of 'fraternity' in the whole film, but "Three Colors: Red" is also quite aware of another infinitely more transcendent thing: destiny. Again, with its fascinating visionary depth and articulate human drama, "Three Colors: Red" is the best film in the trilogy, and is also a fitting swan song for Krzysztof Kieslowski, who sadly passed away far too soon.

FINAL RATING