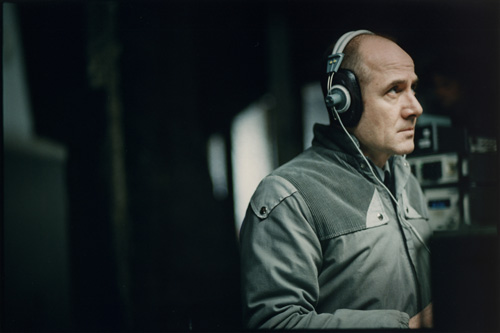

Intently listening.

Intently listening.A second viewing.

With Francis Ford Coppola's "The Conversation" being its closest cinematic kin, "The Lives of Others", one of the decade's best films and is also a stunning directorial debut by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, is also exceptional in its well-calculated thrills and is touchingly human in its very essence, which more or less separates it from the aforementioned paranoid classic. "The Lives of Others", with its beautiful emotional center that develops and permeates throughout the film, elevates itself from merely being a strongly-acted piece about the iron-fisted times of the German Democratic Republic into a genuinely transcendent piece about the beauty and mystery of human nature.

Set in 1980's East Germany during the times when German socialism is at an all-time high, privacy invasions through surveillances a commonality, and the destruction of the Berlin Wall nothing but an unrealized fantasy. Wiesler, played by the late Ulrich Muhe in a truly underrated performance that I think should be considered as one of the best in the last twenty years or so, is a seemingly cold surveillance expert and Stasi (German secret police) agent with principles that are well-intact, objective methods for investigations that are proven to be effective, and a solitary way of life. For many years, he has been a success in his field, capable of making suspected radicals squeal the names of associates and potential inciters of rebellion against the state confess to whatever they know. But despite of his strengths and an ability to thoroughly dissect, he struggles to connect.

"Stay a little while", says Wiesler as he futilely tries to convince a cheap prostitute to stay with him after they had a stiff sexual intercourse. Ironically, he is a man that technically controls the fate of those he interrogates and wiretaps but can't even guide his own. Here is a man whose existence has been rendered almost meaningless by his work but still oblivious of the fact.

Enter Dreyman (Sebastian Koch), a playwright, and Christa-Maria (Martina Gedeck), a stage actress: a couple that has been ordered to be put under surveillance technically because of radical suspicions but is really about Minister Hempf's (Thomas Thieme), a Stasi superior, ulterior intent to personally own Christa-Maria for his own sexual fulfillment.

Wiesler willingly signed up for the former but never for the latter; and to make his situation even more conflicted, Dreyman is slowly turning into the serious GDR critic that he was always suspected to be. And to make it even worse, Wiesler is silently being drawn into the couple's personal world plagued by emotional imperfections and forces they cannot control but nonetheless proved to fit Wiesler's concept of transcendent human connection. Furthermore, it's a world that Wiesler has never experienced before let alone felt. They represent his most hidden of hopes and the very truth of his own being.

But there's one personal challenge for him: He mustn't fly too close to the fire. Should he be the silently harsh Stasi agent that he always was? Or should he be a silent crusader for the sake of what's more righteous and more beautiful, at least for him?

From such a simple character as Wiesler, in a performance by Ulrich Muhe that is brilliantly understated and flawlessly complete, "The Lives of Others" has brilliantly embraced emotional importance and an unconditional faith in humanity more than the usual conundrums of a suspense-filled affair.

Director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck once mentioned in an interview (and is also mentioned briefly in the film) that he was always fascinated of the fact that Vladimir Lenin, as it was told, can't seem to bring himself into finishing the Russian revolution every time he listens to Beethoven's 'Appasionata', his favorite musical piece of all time.

If the power of art can bring or manipulate people to such momentary departures from who they really are, how powerful can it really be? But is that really the case? What if art and beauty, in fact, brings people closer into what they really are? "The Lives of Others" sided with the potential idea that humans are innately good and that humanity, for whatever it has been all throughout history, always strives for an inner truth. The oblivious Wiesler unconsciously did, and unlike Lenin, his 'Appasionata' never stopped playing.

No comments:

Post a Comment