Crown.

For the record, this is the first time that I have watched an Andrei Tarkovsky film and I must say that it was quite a spellbinding first encounter. Both confusing and enthralling at the same time, "Stalker" is a timeless meditation on beliefs that contradict what's empirically perceived and is also a deep exploration of intellectual apprehension. Part-fantasy, part-science fiction and, in some ways, a quasi-religious discourse, this film is unique not just because of the otherworldly concepts that has established the film's visual texture but also because of the density of what it speaks of.

Although painfully slow in its pacing, "Stalker" is never boring because of the quite stunning ideas that it presents. The film, about two tormented intellectuals and how they are guided by the titular character towards the 'Zone' (a place that is said to have the ability to grant wishes), is an adventure of immense consequences. It is a soul-searching trek towards a proverbial 'end of a rainbow' yet it is also a melancholic journey made infinitely more compelling by the characters' constant polemics.

At times, I even found the conversations and arguments between the three characters to be even more fascinating than what their mission awaits them. This, I think, is the thing that makes auteurs like Tarkovsky very, very exceptional. Aside from their command of the visuals, they are also in control of which language their films would speak. And in "Stalker's" case, Tarkovsky mainly chose the language of metaphysics to further the film's profound abstraction.

With the film mainly concerned about the unanswerable inquiries about the meaning of life and the anxiety of both knowing and feeling too much (represented by the two intellectuals, one a writer and the other a physicist), it was quite obvious at certain times that the characters' utterances are personal musings coming from Tarkovsky himself. At one point, the film has even discoursed about the unselfishness of art and the shallowness of technology (the writer character claimed that technology is nothing but an 'artificial limb' which makes people work less and eat more); with Tarkovsky the auteur at the helm, that particular statement is obviously all too personal that it seem out of place in a film that deals with monolithic ideas about life in the context of despair. But nonetheless, it's also all too refreshing. This is why true auteurs and no one else can best capture intimate artistry both at its most divine and at its most turbulent; they just know it all too well.

Now if there's a term that would best describe the feat of creating this film, then I think it would be 'miraculous'. A convergence of imagery and content, "Stalker" is masterful not just because of the technical craftsmanship that comes with it or the weight of its ideas but because of the equal distribution of both and the patience of how they were balanced. And then there are also the locations that have made the film even more special. With the 'Zone' seemingly taking on a life and character of its own as the film progresses, the way the place was visually presented is quite impressive because of how three-dimensional it was. With a naturally pervading sense of unpredictability, acute danger and, ultimately, of spiritual transcendence, the 'Zone' has been the strong backbone of the film.

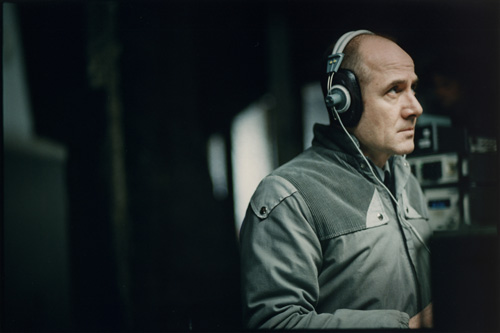

Shooting in ruins, dank tunnels and dark sewers, Tarkovsky and company has molded the reality (or unreality) of the 'Zone' in a way that's mystical yet also consistently dystopian. Also, there were some great performances in it too, particularly that of Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy as the 'stalker' himself.

In some ways, the film's final minutes, at least for me, seems to be a subtle commentary regarding the irrationality of religion (with that enduring image of one of the characters wearing a crown of thorns on his head as if emulating Christ) and the outlandish belief towards both the unknown and the unseen. But despite of the film's flowing cynicism, "Stalker" still echoes hope even at its subtlest. Amid the film's overwhelming sense of intellectualism, it has at least succeeded to be emotionally eloquent. Though the film has left many questions in its wake, it offers closure on an emotional level. That, for me, is what's more important.

FINAL RATING